The benchmark game: how AI leaders use evaluation scores to manage perception

An investigation into how AI companies use benchmarks to shape perception, influence investors, and manage competitive narratives.

AI benchmarks are meant to be objective measures of progress.

In practice, they have become one of the industry’s most effective tools for shaping public perception and competitive narratives. This investigation examines how major AI labs — OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, and Mistral — use benchmark releases as strategic communication weapons rather than neutral scientific disclosures.

Benchmarks were once useful — now they are marketing surfaces

In the early days of deep learning, benchmarks like ImageNet, SQuAD, and GLUE meaningfully differentiated models. Today, the situation is different:

- most benchmarks are saturated

- many can be gamed through training data

- some leak into pretraining corpora

- almost none reflect real-world utility

- yet benchmark charts dominate blog posts, press briefings, investor decks, and “model cards”

The benchmark has shifted from measurement tool to marketing asset.

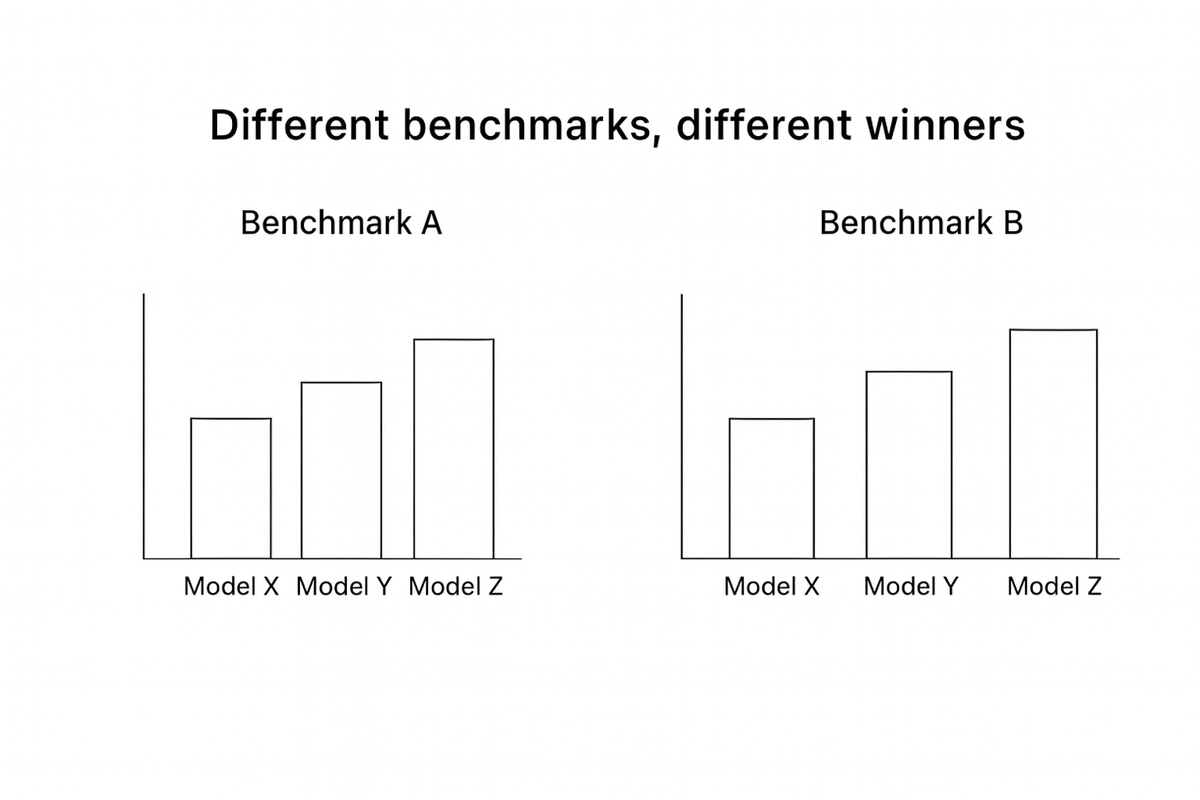

The illusion of comparability

When a company publishes a chart showing its model outperforming competitors, several quiet choices often sit behind the bars:

- which benchmarks to include

- which to omit

- which versions to test

- which prompts were used

- whether handcrafted exemplars were allowed

- whether temperature was zero or tuned

- whether system prompts were engineered

- how many trials were averaged

- what counts as a “pass”

None of this is standardised.

All of it influences the narrative.

There is no global agreement about how to test anything.

So each company constructs its own scoreboard — and invariably wins on it.

“Benchmark bundles”: the new PR weapon

Labs increasingly release carefully curated benchmark bundles, designed to present a model as universally superior. These bundles often:

- mix real benchmarks with synthetic in-house tests

- include obscure datasets known to favour a specific model

- quietly drop benchmarks where performance is weaker

- highlight percentage improvements without showing raw scores

- present wide error bars as definitive victories

To the average reader, the charts look authoritative.

To insiders, they are a branding exercise.

The timing tells its own story

Benchmark releases consistently coincide with:

- funding rounds

- product launches

- competitive responses

- partnership announcements

- public scrutiny or reputational dips

A suspiciously common pattern emerges:

- Company A releases a new model with benchmark charts claiming it leads.

- Company B responds days or weeks later with new charts showing it leads.

- Both sets of charts contradict each other.

- The press covers the conflict as evidence of rapid progress.

- Investors reward both companies for appearing to win.

The benchmarks do not change reality.

The benchmarks change narrative.

When benchmarks leak into training data

A growing problem is contamination: when the benchmark dataset appears in the model’s pretraining corpus.

This inflates scores without improving general ability.

It is rarely disclosed.

And when caught, it is framed as an unavoidable artefact of scale rather than a methodological failure.

Benchmark inflation is not cheating — it is the industry norm.

The regulatory implications

Governments increasingly ask AI companies to “prove capability” when discussing safety, risk, or deployment.

Companies present benchmark charts.

If the charts are strategically constructed:

- regulators may misunderstand actual risk levels

- claims of “emergent capabilities” can be overstated

- claims of “alignment progress” can be unsubstantiated

- discussions about AGI proximity are skewed by selective evidence

Benchmarks shape not just public narrative, but policy.

Conclusion: The benchmark game

Benchmarks were meant to measure progress.

They now measure opportunity.

For AI companies, benchmarks serve three strategic purposes:

- Influencing investors — a model that “beats GPT-4” raises valuations overnight.

- Managing competition — selective benchmarks create the impression of leadership.

- Framing public discourse — charts create an aura of scientific objectivity, even when the methodology is opaque.

The result is a market where the least standardised metrics carry the most influence.

The charts are not lies.

They are carefully curated truths — optimised for perception, not clarity.

- For background on how model behaviour works, see our Explanation on chatbots.

- For Rumours that rely heavily on benchmark claims, see our analysis of “Llama 4 is AGI-capable” and similar posts.